Excerpt from Boston University Hospitality Review

The Service Revolution has begun

The Industrial Revolution, started in the late 18th century, dramatically increased our standard of living by making high-quality, low-cost manufactured goods available to the masses. Today, our economies seem to be facing a turning point, but now in the service sector. Technologies rapidly become smarter and more powerful, and at the same time, they get smaller, lighter, and cheaper. These include hardware such as physical robots, drones, and wearable technologies, as well as code and software related to analytics, speech processing, image processing, virtual and augmented reality, cloud technologies, mobile technologies, geo-tagging, robotic process automation (RPA), low-code platforms, and machine learning. Together, these technologies will transform virtually all service sectors. Service robots and artificial intelligence (AI), combined with these technologies, will lead to rapid innovation that can dramatically improve the customer experience, service quality, and productivity all at the same time (Wirtz & Zeithaml, 2018).

Robot- and AI-delivered service offers unprecedented economies of scale and scope as the bulk of the costs are incurred in their development. Physical robots cost a fraction of adding headcount, and virtual robots (e.g., chatbots and virtual agents) can be scaled at close to zero incremental costs. Such dramatic salability does not only apply to virtual service robots such as chatbots but also to “visible” ones such as holograms. For example, an airport could install a hologram-based humanoid service robot every 50 meters to assist passengers and answer common questions (e.g., provide arrival information and directions to check-in counters) in all common languages. These holograms only require low-cost hardware (i.e., a camera, microphone, speaker, and projector), and do not take up floor space. (Travelers could push their baggage carts through a hologram when it gets crowded.)

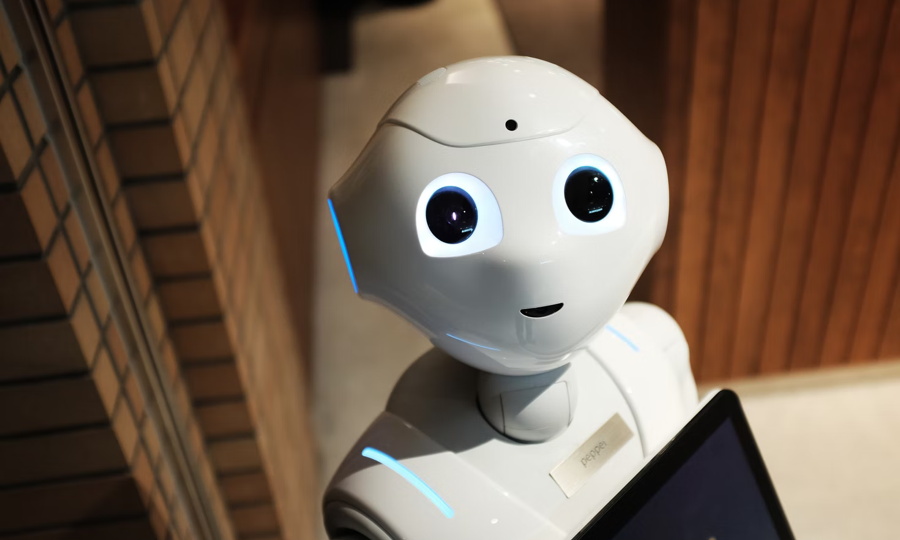

Already, many firms show eager interest in experimenting with service robots. For example, in hotels lobbies, humanoid robots may be used to welcome guests, provide information, and entertain guests. At airports, they scan boarding passes and help passengers to find the right departure gate. Self-moving check-in kiosk robots detect busy areas and autonomously go there to help passengers reduce waiting time (Bruhn et al., 2020).

Such robots are the beginning of the Service Revolution. Similar to the shift that started in the Industrial Revolution from craftsmen to mass production, we believe an accelerated shift in the service sector towards robot- and AI-delivered services is imminent. The exciting prospect is that many services, including hospitality, healthcare, and education, are likely to become available at much lower prices and better quality. Consumers will be the big beneficiaries.

How will customer interactions with service robots differ from those with traditional self-service technologies?

Service robots have been defined as “system-based autonomous and adaptable interfaces that interact, communicate and deliver service to an organization’s customers” (Wirtz et al., 2018). These abilities differentiate service robots from traditional self-service technologies (SSTs) we are familiar with in the context of ticketing machines, websites, and apps. As shown in Table 1, service robots can deal with unstructured interactions and guide customers through their service journey. For example, a ticketing robot will not let customers get stuck as it can ask clarifying questions (e.g., “Is your return trip today? Can you travel off-peak?”) and can even recover customer errors (e.g., a wrong button pressed or incorrect information entered). For most standard services, customers will interact with service robots much like with service employees do (e.g., “I need a same-day return ticket” and “Can I use Apple Pay?”).

Table 1. Contrasting Service Robots with Traditional Self-Service Technologies

| Service Aspect | Self-Service Technologies (SSTs) | Service Robots |

| Customer Service Scripts and Roles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Customer Error Tolerance |

|

|

|

|

|

| Service Recovery Capability |

|

|

How will customer interactions With Service Robots Differ from Those With Human Service Staff?

Robots are not able to feel and express real emotions. This is important in certain services whereby the academic literature distinguishes between deep acting (i.e., employees displaying real emotions) and surface acting (i.e., they show superficial and not deeply felt emotional responses) (Wirtz & Jerger, 2016). In contrast, a robot’s emotions are just displayed and not authentic. Consumers generally know this and respond accordingly. On the other hand, robots can surface act and consistently be pleasant; they are not prone to emotional burnout. This may make robots perform better than humans in jobs that require the display of surface-acted emotions. Other significant differences are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Contrasting Frontline Employees with Service Robots

| Dimension | Service Employees | Service Robots |

| Training and Learning |

|

|

| Customer Experience |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Firm Strategy |

|

|

|

|

Click here to read complete article at Boston University Hospitality Review.